Section 14: Simultaneous Equations Models

General notes

I really like Woolridge for this material. His notation is a bit different from the notes and Greene, but his writing is really clean and simple.

The canonical example

In many settings, the relationships we wish to investigate are more complex than a simple one-equation linear regression of \(y_t\) on an intercept and an exogenous variable \(x_t\). We’ve already discussed one example of further complexity—when \(x_i\) is endogenous—during our instrument variables (IV) and two-stage least squares (2SLS) section. We now consider a second, more general setting wherein the relationships that we wish to econometrically explore are caught up in a system of equations.

One of the classic examples, which Max already showed you in class, is the system of demand and supply for a good: \[ \begin{aligned} \text{Demand:} \quad & q_{d,t} = \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 p_t + \varepsilon_{d,t} \\ \text{Supply:} \quad & q_{s,t} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 p_t + \varepsilon_{s,t} \\ \text{Equilibrium:} \quad & q_{d,t} = q_{s,t} = q_t \end{aligned} \] These equations are known as the structural equations for the system—they hold the structural parameters that we would like to estimate.

We can simplify the system by substituting in the third market-clearing equation into the other two equations \[ \begin{aligned} \text{Demand:} \quad & q_{t} = \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 p_t + \varepsilon_{d,t} \\ \text{Supply:} \quad & q_{t} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 p_t + \varepsilon_{s,t} \\ \end{aligned} \]

The challenge here is that we are unable to separate demand shocks from supply shocks—meaning price and quantity (our variables of interest) are correlated with both error terms and are thus endogenous. To see this fact, solve for \(p_t\) and \(q_t\): \[ \begin{aligned} p_{t} &= \dfrac{\beta_0 - \alpha_0}{\alpha_1 - \beta_1} + \dfrac{\varepsilon_{d,t} - \varepsilon_{s,t}}{\alpha_1 - \beta_1} \\[0.8em] q_{t} &= \dfrac{\alpha_1 \beta_0 - \alpha_0 \beta_1}{\alpha_1 - \beta_1} + \dfrac{\alpha_1 \varepsilon_{d,t} - \beta_1 \varepsilon_{s,t}}{\alpha_1 - \beta_1} \end{aligned} \] Thus price is a function of both supply and demand shocks (make sense)—as is quantity. What we need is a lever (perhaps instrument?) that is exclusive to one channel—either supply or demand. If this lever only affect supply, then we will observe different sets of quantity and price without any movement in the demand curve. We can then use these different sets of quantity and price to trace out the demand curve. More formally: we need a variable \(x_t\) that moves around supply without affecting demand.1 \[ \begin{aligned} \text{Demand:} \quad & q_{t} = \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 p_t + \varepsilon_{d,t} \\ \text{Supply:} \quad & q_{t} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 p_t + \beta_2 x_t + \zeta_{s,t} \end{aligned} \] Now we have a hope of estimating the structural demand parameters. However, we still will not be able to consistently estimate the structural supply parameters.

The general problem

Let’s setup a more general formulation for estimating systems of equations.

Setup

In general, we will write a system of \(M\) simultaneous equations for \(M\) endogenous variables \(y_{1,t}\), …, \(y_{M,t}\) and \(K\) exogenous variables2 \(x_{1,t}\), …, \(x_{K,t}\) in its structural form as:3 \[ \begin{aligned} \gamma_{11} y_{1,t} + \cdots + \gamma_{M1} y_{M,t} + \cdots + \beta_{11} x_{1,t} + \cdots + \beta_{K1} x_{K,t} =& \varepsilon_{1,t} \\ \gamma_{12} y_{1,t} + \cdots + \gamma_{M2} y_{M,t} + \cdots + \beta_{12} x_{1,t} + \cdots + \beta_{K2} x_{K,t} =& \varepsilon_{2,t} \\ \vdots& \\ \gamma_{1M} y_{1,t} + \cdots + \gamma_{MM} y_{M,t} + \cdots + \beta_{1M} x_{1,t} + \cdots + \beta_{KM} x_{K,t} =& \varepsilon_{M,t} \end{aligned} \] which we can write more succinctly as \[ \mathbf{y}_t' \boldsymbol{\Gamma} + \mathbf{x}_t' \mathbf{B} = \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t' \]

We can solve this system for the \(M\) endogenous variables \(\mathbf{y}\) by post-multiplying by \(\boldsymbol{\Gamma}^{-1}\): \[ \begin{aligned} \mathbf{y}_t' \boldsymbol{\Gamma} + \mathbf{x}_t' \mathbf{B} &= \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t' \\[0.4em] \mathbf{y}_t' \boldsymbol{\Gamma}\boldsymbol{\Gamma}^{-1} + \mathbf{x}_t' \mathbf{B}\boldsymbol{\Gamma}^{-1} &= \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t'\boldsymbol{\Gamma}^{-1} \\[0.4em] \mathbf{y}_t' &= - \mathbf{x}_t' \mathbf{B}\boldsymbol{\Gamma}^{-1} + \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t'\boldsymbol{\Gamma}^{-1} \\[0.4em] \mathbf{y}_t' &= \mathbf{x}_t' \boldsymbol{\Pi} + \mathbf{v}_t' \end{aligned} \] which gives our reduced-form equations.

Finally, to take into account our \(T\) observations, \[ \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{Y} & \mathbf{X} & \mathbf{E} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{y}_1' & \mathbf{x}_1' & \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_1' \\ \mathbf{y}_2' & \mathbf{x}_2' & \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_2' \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots \\ \mathbf{y}_T' & \mathbf{x}_T' & \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_T' \\ \end{bmatrix} \] which gives us \[ \mathbf{Y} \boldsymbol{\Gamma} + \mathbf{X} \mathbf{B} = \mathbf{E} \] We will assume strict exogeneity, \(\mathop{\boldsymbol{E}}\left[ \mathbf{E} | \mathbf{X} \right] = 0\). The reduced form is \[ \mathbf{Y} = \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\Pi} + \mathbf{V} \]

Identification: The problem

We can easily and consistently estimate the parameters from the reduced-form equations (\(\boldsymbol{\Pi}\)) via \(\hat{\boldsymbol{\Pi}} = (\mathbf{X}'\mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{Y}\). However, we usually want to learn about the structural parameters—not the reduced-form parameters. You might be tempted to think we can simply back out consistent estimates for the structural parameters using out consistent estimates for the reduced-form parameters. But there’s a problem here: our reduced-form equation does not guarantee a unique set of structural estimates. Observe:

- Recall that \(\boldsymbol{\Pi} = - \mathbf{B} \boldsymbol{\Gamma}^{-1}\).

- Post-multiply our structural equation by some arbitrary nonsingular matrix \(\mathbf{F}\): \[ \begin{aligned} \mathbf{Y} \boldsymbol{\Gamma} \mathbf{F} + \mathbf{X} \mathbf{B} \mathbf{F} &= \mathbf{E} \mathbf{F} \\ \mathbf{Y} \tilde{\boldsymbol{\Gamma}} + \mathbf{X} \tilde{\mathbf{B}} &= \tilde{\mathbf{E}} \end{aligned} \]

- Solve for the reduced form of this alternate structural model: \[ \begin{aligned} \mathbf{Y} \tilde{\boldsymbol{\Gamma}} \tilde{\boldsymbol{\Gamma}}^{-1} + \mathbf{X} \tilde{\mathbf{B}} \tilde{\boldsymbol{\Gamma}}^{-1} &= \tilde{\mathbf{E}}\tilde{\boldsymbol{\Gamma}}^{-1} \\[0.2em] \mathbf{Y} &= - \mathbf{X} \mathbf{B} \mathbf{F} \mathbf{F}^{-1} \boldsymbol{\Gamma}^{-1} + \mathbf{E} \mathbf{F} \mathbf{F}^{-1} \boldsymbol{\Gamma}^{-1} \\[0.2em] \mathbf{Y} &= - \mathbf{X} \mathbf{B} \boldsymbol{\Gamma}^{-1} + \mathbf{E} \boldsymbol{\Gamma}^{-1} \\[0.2em] \mathbf{Y} &= \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\Pi} + \mathbf{V} \end{aligned} \]

Thus, the two different sets of structural equations produce the same reduced form. This result is bad news if you are trying to learn anything about the structural-form parameters. So what can we do? We need to make some assumptions/exclusions that allow us to rule out any \(\mathbf{F}\) except for the identity matrix.

Another way to think about this problem: We know that we can consistently estimate the \(K \times M\) reduced-form parameters and the \(M\times M\) reduced-form covariance matrix, which means we “know” \(KM + \frac{1}{2}(M+1)M\) parameters. We want to know the \(M\times M\) parameters in \(\boldsymbol{\Gamma}\), the \(K\times M\) parameters in \(\mathbf{B}\), and the \(M\times M\) parameters in \(\boldsymbol{\Sigma}\)—meaning we do not know \(M^2 + KM + \dfrac{1}{2}(M+1)M\) structural parameters. The difference between the numbers of “known” and “unknown” parameters is \(M^2\)—there are \(M^2\) more unknown parameters than known parameters. Hence the need to make some assumptions.

Identification: The solution(s)

Max and Greene provide a list of five solutions to our identification problem.

- Normalization

- Identities

- Exclusions

- Linear restrictions

- Restriction on the disturbance covariance matrix

We’ll focus on (1) and (2–4).

A single equation

Let’s focus on a single equation from our system, equation \(i\): \[ \mathbf{Y} \boldsymbol{\Gamma}_i + \mathbf{X} \mathbf{B}_i = \mathbf{e}_i \] or perhaps more clearly4 \[ \gamma_{1i} y_1 + \gamma_{2i} y_2 + \cdots + \gamma_{Mi} y_M + \beta_{1i} x_1 + \beta_{2i} x_2 \cdots + \beta_{MK} x_K = \varepsilon_i \]

Normalization

The first restriction that we will make is the normalization restriction, which simply sets the coefficient on one of our endogenous variables to \(1\).5 The norm6 is that the coefficient on the \(i\)th endogenous variable gets normalized, though it really doesn’t matter which one you choose. Your structural model should actually inform this choice (see Woolridge chapter 9 for a really nice write up here).

Let’s focus on the \(i=1\) equation and normalize \(\gamma_{11} = 1\). Then structural equation \(i=1\) becomes \[ y_1 + \gamma_{21} y_2 + \cdots + \gamma_{M1} y_M + \beta_{11} x_1 + \beta_{21} x_2 \cdots + \beta_{MK} x_K = \varepsilon_1 \] And we now only have a deficit of \(M(M-1)\) unknown parameters (relative to the number of known parameters). How easy was that?

Restrictions

I’m going to lump together identities, exclusions, and linear restrictions. The gist of the game here is we have too many parameters. Hopefully there are some reasonable restrictions to make—not all variables affect all other variables (and thus can be excluded), some parameters are equal or linearly related, etc.

First, let’s define a matrix filled with all of our structural-form parameters: \[\boldsymbol{\Delta} = \begin{bmatrix}\boldsymbol{\Gamma} \\ \mathbf{B} \end{bmatrix}\] The \(i\)th column of \(\boldsymbol{\Delta}\) gives the structural-form parameters in the \(i\)th equation, i.e., \[\boldsymbol{\Delta}_i = \begin{bmatrix}\boldsymbol{\Gamma}_i \\ \mathbf{B}_i \end{bmatrix}\]

Now define a matrix \(\mathbf{R}_i\) that imposes all of the restrictions on equation \(i\) (excluding the normalization restriction) such that \[ \mathbf{R}_i \boldsymbol{\Delta}_i = \boldsymbol{0} \]

Example7

For instance, if we have a system of equations \[ \begin{aligned} y_1 &= \gamma_{21} y_2 + \gamma_{31} y_3 + \beta_{11} x_1 + \beta_{31} x_3 + \varepsilon_1 \\ y_2 &= \gamma_{12} y_1 + \beta_{12} x_1 + \varepsilon_2 \\ y_3 &= \beta_{13} x_1 + \beta_{23} x_2 + \beta_{33} x_3 + \beta_{43} x_4 + \varepsilon_3 \end{aligned} \]

The restrictions (ignoring the normalization) imposed in equation 1 are: \(\beta_{21} = 0\) and \(\beta_{41} = 0\). Therefore, \[ \mathbf{R}_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \]

To see this definition of \(\mathbf{R}_1\), post-multiply it by \(\boldsymbol{\Delta}_1\): \[ \mathbf{R}_1 \boldsymbol{\Delta}_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} -1 \\ \gamma_{21} \\ \gamma_{31} \\ \beta_{11} \\ \beta_{21} \\ \beta_{31} \\ \beta_{41} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \beta_{21} \\ \beta_{41} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} \] which replicates our restrictions.

Order condition

The order condition gives us a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for whether the \(i\)th structural equation is identified. The order condition says that a necessary condition for the \(i\)th equation to be identified is \(J_i \geq M-1\), where \(J_i\) is the row dimension of \(\mathbf{R}_i\).

The order condition is a fairly quick and easy way to check whether an equation is identified. Just keep in mind that the order condition is necessary but not sufficient.

Greene formally defines the order condition slightly differently:8 “The number of exogenous variables excluded from equation \(j\) must be at least as large as the number of endogenous variables included in equation \(j\).”

Rank condition

The rank condition provides a necessary and sufficient condition for the \(i\)th equation to be identified. The rank condition is: \[\text{rank}\big(\mathbf{R}_i \boldsymbol{\Delta}\big) = M-1\]

Name calling

Our order condition allows for three possibilities:

- \(J_i < M-1\): Equation \(i\) is under identified.

- \(J_i = M-1\) and \(\text{rank}\big(\mathbf{R}_1 \boldsymbol{\Delta}\big) = M-1\): Equation \(i\) is exactly identified.

- \(J_i > M-1\) and \(\text{rank}\big(\mathbf{R}_1 \boldsymbol{\Delta}\big) = M-1\): Equation \(i\) is over identified.

Example, continued

Returning to our example of three endogenous variables, three equations, and four exogenous variables \[ \begin{aligned} y_1 &= \gamma_{21} y_2 + \gamma_{31} y_3 + \beta_{11} x_1 + \beta_{31} x_3 + \varepsilon_1 \\ y_2 &= \gamma_{12} y_1 + \beta_{12} x_1 + \varepsilon_2 \\ y_3 &= \beta_{13} x_1 + \beta_{23} x_2 + \beta_{33} x_3 + \beta_{43} x_4 + \varepsilon_3 \end{aligned} \] and \[ \mathbf{R}_1 = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \]

We can check the order condition for the first equation: \(J_1 = 2\) (the number of rows in \(\mathbf{R}_1\)), and \(M-1 = 3-1 = 2\), so \(J_1 = M-1\). We exatly satisfy the order condition. However, we still need to check the rank condition.

\[ \mathbf{R}_1 \boldsymbol{\Delta} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} -1 & \gamma_{12} & \gamma_{13} \\ \gamma_{21} & -1 & \gamma_{23} \\ \gamma_{31} & \gamma_{32} & -1 \\ \beta_{11} & \beta_{12} & \beta_{13} \\ \beta_{21} & \beta_{22} & \beta_{23} \\ \beta_{31} & \beta_{32} & \beta_{33} \\ \beta_{41} & \beta_{42} & \beta_{43} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \beta_{21} & \beta_{22} & \beta_{23} \\ \beta_{41} & \beta_{42} & \beta_{43} \end{bmatrix} \]

Now we impose any restrictions found in the structural equations. The first column is all zeros because \(\beta_{21} = 0\) and \(\beta_{41} = 0\) by assumption. Notice that the second structural equation also sets \(\beta_{22}=0\) and \(\beta_{42}=0\). Finally, the third structural equation does not have any restrictions that affect \(\mathbf{R}_1 \boldsymbol{\Delta}\). Imposing these restrictions, we now have

\[ \mathbf{R}_1 \boldsymbol{\Delta} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & \beta_{23} \\ 0 & 0 & \beta_{43} \end{bmatrix} \] which has at most rank 1 (if either \(\beta_{23}\) or \(\beta_{43}\) are not equal to zero). Because \(M-1=3-1=2\), equation 1 fails the rank condition and is therefore not identified in this system of equations.

Checking identification

Woolridge9 provides a nice four-step process for checking whether the \(i\)th equation in the system is identified:

- Set one of the parameters for the endogenous variables (i.e., one of the \(\gamma_{mi}\)) to one (normalization).

- Define the \(J_i \times (M+K)\) matrix \(\mathbf{R}_i\) that imposes all of the restrictions for equation \(i\).

- If \(J_i < M-1\), then equation \(i\) is not identified (under identified).

- If \(J_i \geq M-1\), then equation \(i\) might be identified.

- Let \(\boldsymbol{\Delta}\) be the matrix of all structural parameters with only the normalization restrictions applied.

- Compute \(\mathbf{R}_i \boldsymbol{\Delta}\).

- Impose the restrictions in the entire system.

- Check the rank condition, i.e., \(\text{rank}\big(\mathbf{R}_i \boldsymbol{\Delta}\big) = M-1\).

Simultaneous simulation

Let’s bake some data so we can apply our newly learned theory.

First, it will be helpful (necessary) to have an actual set of equations. So here is one. \[ \begin{aligned} y_{1} &= \gamma_{21} y_{2} + \beta_{21} x_2 + \beta_{31} x_3 + \varepsilon_1 \\ y_{2} &= \gamma_{32} y_{3} + \beta_{12} x_1 + \beta_{22} x_2 + \varepsilon_2 \\ y_{3} &= \gamma_{13} y_{1} + \beta_{13} x_1 + \varepsilon_3 \end{aligned} \]

I’ll let you check the rank conditions for each of the equations. They should pass.

Let’s write out the structural and reduced forms in matrix form.

\[ \begin{aligned} \begin{bmatrix} y_1 & y_2 & y_3 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} -1 & 0 & \gamma_{13} \\ \gamma_{21} & -1 & 0 \\ 0 & \gamma_{32} & -1 \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} x_1 & x_2 & x_3 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 0 & \beta_{12} & \beta_{13} \\ \beta_{21} & \beta_{22} & 0 \\ \beta_{31} & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} = - \begin{bmatrix} \varepsilon_1 & \varepsilon_2 & \varepsilon_3 \end{bmatrix} \end{aligned} \]

Which implies the reduced form \[ \begin{aligned} \begin{bmatrix} y_1 & y_2 & y_3 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} x_1 & x_2 & x_3 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 0 & \beta_{12} & \beta_{13} \\ \beta_{21} & \beta_{22} & 0 \\ \beta_{31} & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} -1 & 0 & \gamma_{13} \\ \gamma_{21} & -1 & 0 \\ 0 & \gamma_{32} & -1 \end{bmatrix}^{-1} - \begin{bmatrix} \varepsilon_1 & \varepsilon_2 & \varepsilon_3 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} -1 & 0 & \gamma_{13} \\ \gamma_{21} & -1 & 0 \\ 0 & \gamma_{32} & -1 \end{bmatrix}^{-1} \end{aligned} \]

Parameterization

We can use this reduced form to generate data, but first we need to define some parameters. \[ \begin{aligned} y_{1} &= 2 y_{2} + 3 x_2 + 5 x_3 + \varepsilon_1 \\ y_{2} &= 3 y_{3} + 1 x_1 + 4 x_2 + \varepsilon_2 \\ y_{3} &= 1 y_{1} + 2 x_1 + \varepsilon_3 \end{aligned} \]

Thus, the parameters in \(\boldsymbol{\Gamma}\) are: \[ \boldsymbol{\Gamma} = \begin{bmatrix} -1 & 0 & \gamma_{13} \\ \gamma_{21} & -1 & 0 \\ 0 & \gamma_{32} & -1 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} -1 & 0 & 1 \\ 2 & -1 & 0 \\ 0 & 3 & -1 \end{bmatrix} \] And the parameters in \(\mathbf{B}\) are: \[ \mathbf{B} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & \beta_{12} & \beta_{13} \\ \beta_{21} & \beta_{22} & 0 \\ \beta_{31} & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 2 \\ 3 & 4 & 0 \\ 5 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \]

Now let’s set it all up in R.

First the general setup.

# General R setup ----

# Options

options(stringsAsFactors = F)

# Load new packages

library(pacman)

p_load(ggmap, leaflet)

# Load old packages

p_load(dplyr, ggplot2, ggthemes, parallel, magrittr, viridis)

# My ggplot2 theme

theme_ed <- theme(

legend.position = "bottom",

panel.background = element_rect(fill = NA),

# panel.border = element_rect(fill = NA, color = "grey75"),

axis.ticks = element_line(color = "grey95", size = 0.3),

panel.grid.major = element_line(color = "grey95", size = 0.3),

panel.grid.minor = element_line(color = "grey95", size = 0.3),

legend.key = element_blank())

# My directories

dir_14 <- "/Users/edwardarubin/Dropbox/Teaching/ARE212/Section14/"Now the structural parameters.

# Define the structural parameters ----

# Gamma

Gamma <- matrix(

data = c(-1, 0, 1, 2, -1, 0, 0, 3, -1),

nrow = 3,

byrow = T

)

# Beta

Beta <- matrix(

data = c(0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 0, 5, 0, 0),

nrow = 3,

byrow = T

)Generate data

Now let’s generate the three \(x_k\) variables and the disturbances \(\varepsilon_{m}\) from standard random normal distributions. We want 10,000 observations.

# Generate data ----

# Set the sample size

N <- 1e3

# Set a seed

set.seed(12345)

# Generate the data for X and E

x_df <- data_frame(

x1 = rnorm(N),

x2 = rnorm(N),

x3 = rnorm(N)

)

e_df <- data_frame(

e1 = rnorm(N),

e2 = rnorm(N),

e3 = rnorm(N)

)Now we will use the reduced form to generate our \([\mathbf{y}_1,\, \mathbf{y}_2,\, \mathbf{y}_3]\) variables.

# Generate the y variables

y_mat <- (-1) * as.matrix(x_df) %*% Beta %*% solve(Gamma) -

as.matrix(e_df) %*% solve(Gamma)

# Force to data frame

y_df <- y_mat %>% as_data_frame()

names(y_df) <- c("y1", "y2", "y3")

# Join the data together

the_df <- bind_cols(y_df, x_df)Estimation

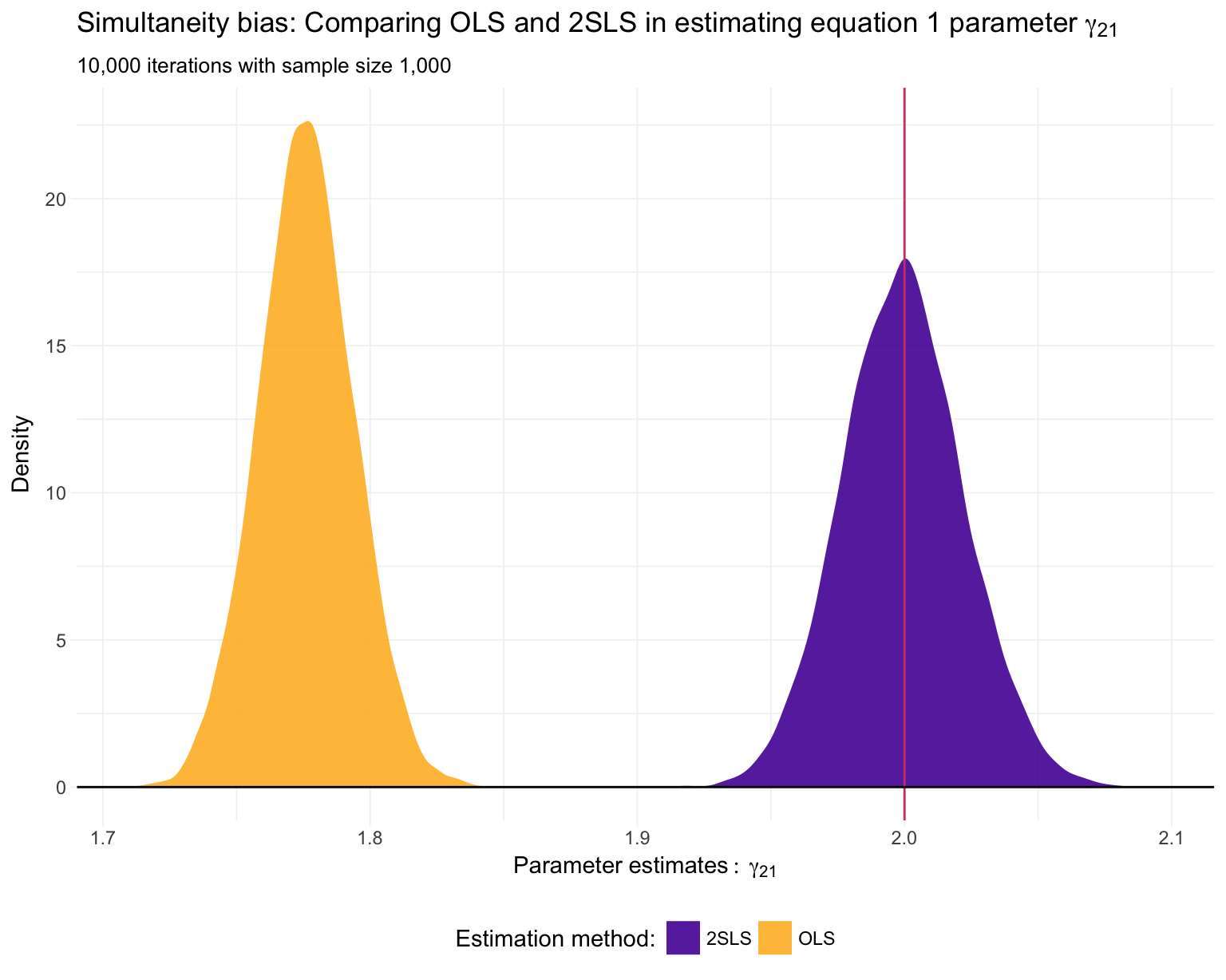

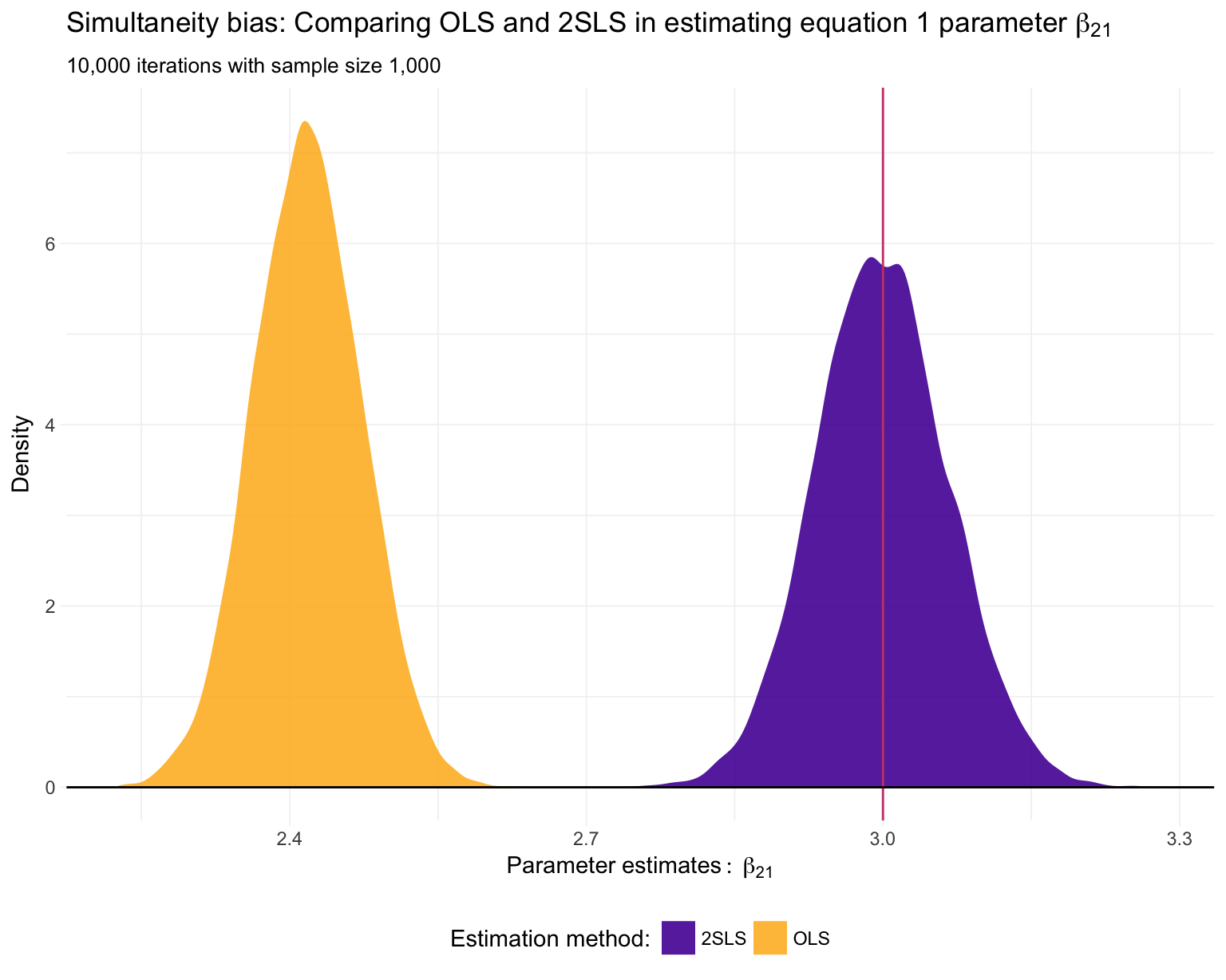

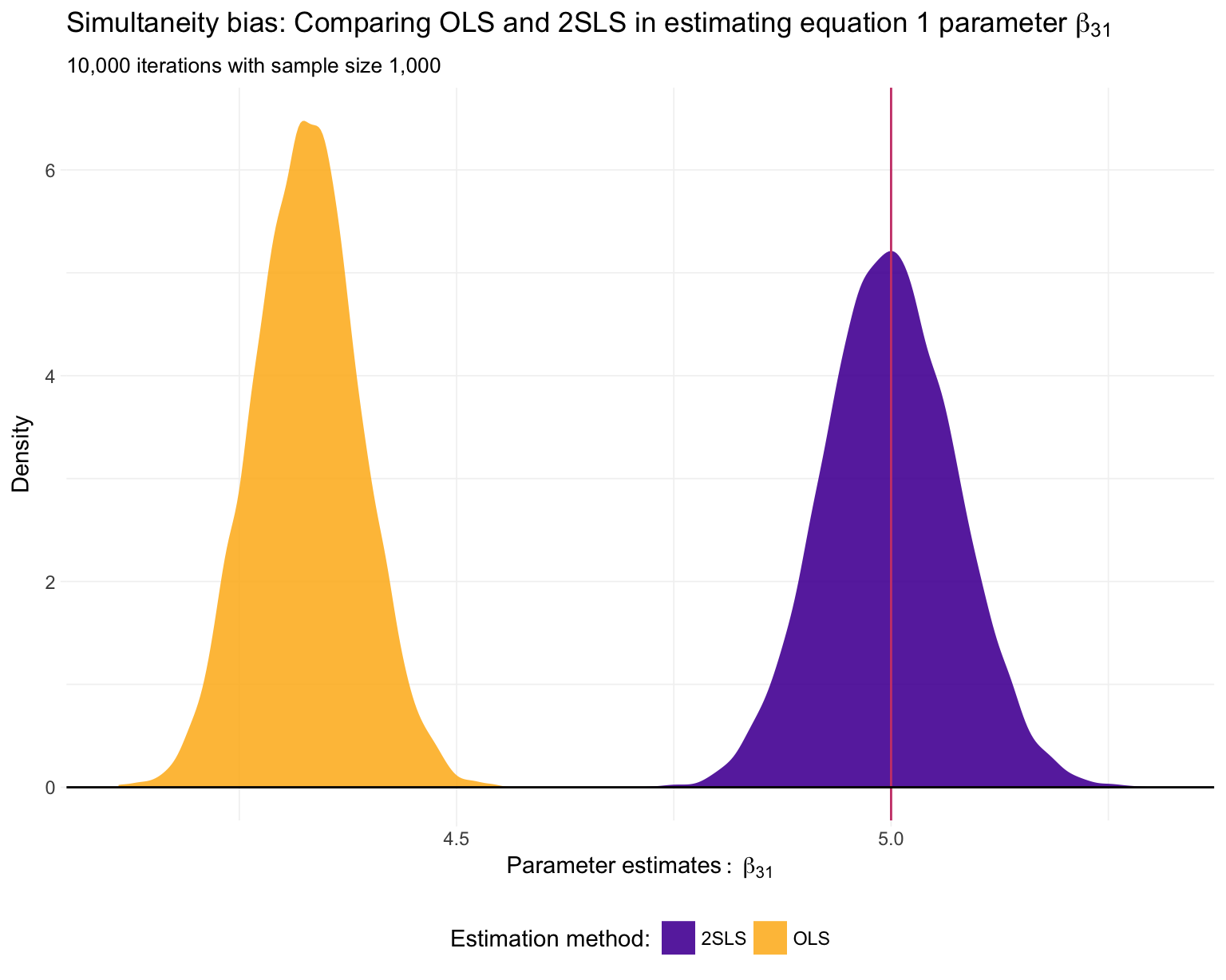

Let’s estimate the parameters in the first equation. Keep in mind that truth in this simulation is \(\gamma_{21} = 2\), \(\beta_{21} = 3\), and \(\beta_{31} = 5\).

OLS

First, let’s try plain OLS to estimate the parameters in the first equation. OLS here is exactly what we’ve been doing throughout this whole course: for equation \(i\), regress the left-hand side variable (\(\mathbf{y}_i\)) on the right-hand side variables (\(\mathbf{Z}_i\), which includes endogenous and exogenous variables on the RHS).

\[ \mathbf{d}_{i,\text{OLS}} = \left( \mathbf{Z}_i'\mathbf{Z}_i \right)^{-1} \mathbf{Z}_i' \mathbf{y}_i' \]

OLS for equation 1:

# The LHS variable in eq. 1

yi <- y_mat[,1]

# The RHS variables in eq. 1

Zi <- bind_cols(y_df[,2], x_df[,2:3]) %>% as.matrix()

# OLS estimates

solve(t(Zi) %*% Zi) %*% t(Zi) %*% yi## [,1]

## y2 1.802818

## x2 2.479916

## x3 4.388147OLS is inconsistent here. Unsurprisingly, our estimates are not right on their parameters.

2SLS

One of the classic solutions to simultaneity bias—particularly when you only care about estimating the parameters in a single equation—is two-stage least squares (2SLS). In this application of two-stage least squares, we are going to instrument (project) the endogenous RHS variables of equation \(i\) with all of the exogenous variables in the system. To make calculation a bit easier, we will actually instrument all RHS variables in equation \(i\) (call this matrix \(\mathbf{Z}_i\)) with all of the exogenous variables in the system (call this matrix \(\mathbf{X}\)). Call the predictions (a.k.a fitted values) from this first stage \(\hat{\mathbf{Z}}_i\). We then regress our LHS dependent variable in equation \(i\) (call this vector \(\mathbf{y}_i\)) on \(\hat{\mathbf{Z}}_i\). In math:

\[ \begin{aligned} \text{Predictions from the first stage:}& \quad \hat{\mathbf{Z}}_i = \mathbf{X} \left( \mathbf{X}'\mathbf{X} \right)^{-1} \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{Z}_i \\ \text{Second-stage estimates for }\boldsymbol{\Delta}_i\text{:}& \quad \mathbf{d}_{i,\text{2SLS}} = \left( \hat{\mathbf{Z}}_i' \hat{\mathbf{Z}}_i \right)^{-1} \hat{\mathbf{Z}}_i' \mathbf{y}_i \end{aligned} \]

# Matrix of all exogenous variables in the system

X <- x_df %>% as.matrix()

# First-stage fitted values

Zi_hat <- X %*% solve(t(X) %*% X) %*% t(X) %*% Zi

# 2SLS estimates

solve(t(Zi_hat) %*% Zi_hat) %*% t(Zi_hat) %*% yi## [,1]

## y2 2.017908

## x2 3.049772

## x3 5.022968Much better!

Simulation

We’ve observed that in a single sample 2SLS gets us much closer to the true parameter estimates than OLS. Let’s use a simulation to confirm that this empirical observation (and the underlying theory) repeat through many samples.10

For this simulation, we want to

- Generate a population of size \(N\)

- Sample from the population with sample size \(n\)

- Estimate OLS and 2SLS on the sample

- Repeat 10,000 times

First, let’s generate the population. I think a 100,000 members will suffice. We can simply steal code from above.

# Simulation ----

# Clean up from the other 'simulation'

rm(N, x_df, e_df, y_mat, y_df, the_df, yi, Zi, X, Zi_hat); gc()## used (Mb) gc trigger (Mb) max used (Mb)

## Ncells 745519 39.9 1168576 62.5 1168576 62.5

## Vcells 1193138 9.2 2928070 22.4 2346069 17.9# Generate population data:

# Set the population size

N <- 1e5

# Set a seed

set.seed(12345)

# Generate the data for X and E

pop_x <- data_frame(

x1 = rnorm(N),

x2 = rnorm(N),

x3 = rnorm(N)

)

pop_e <- data_frame(

e1 = rnorm(N),

e2 = rnorm(N),

e3 = rnorm(N)

)

# Generate the y variables

pop_y <- (-1) * as.matrix(pop_x) %*% Beta %*% solve(Gamma) -

as.matrix(pop_e) %*% solve(Gamma)

# Force to data frame

y_df <- pop_y %>% as_data_frame()

names(y_df) <- c("y1", "y2", "y3")

# Join the data together

pop_df <- bind_cols(y_df, pop_x)

# Clean up

rm(pop_x, pop_e, pop_y, y_df); gc()## used (Mb) gc trigger (Mb) max used (Mb)

## Ncells 745647 39.9 1168576 62.5 1168576 62.5

## Vcells 1793263 13.7 2928070 22.4 2904307 22.2Now we will write a function that carries out tasks (2) and (3).

# Function: Run a single iteration of the simulation

fun_iter <- function(i, data, sample_size) {

# Sample from the population

smpl_df <- sample_n(tbl = data, size = sample_size)

# The LHS variable in eq.1

yi <- smpl_df %>% select(y1) %>% as.matrix()

# The RHS variables in eq. 1

Zi <- smpl_df %>% select(y2, x2, x3) %>% as.matrix()

# OLS estimates

d_ols <- solve(t(Zi) %*% Zi) %*% t(Zi) %*% yi

# Matrix of all exogenous variables in the system

X <- smpl_df %>% select(starts_with("x")) %>% as.matrix()

# First-stage fitted values

Zi_hat <- X %*% solve(t(X) %*% X) %*% t(X) %*% Zi

# 2SLS estimates

d_2sls <- solve(t(Zi_hat) %*% Zi_hat) %*% t(Zi_hat) %*% yi

# Create results data frame

result_df <- rbind(t(d_ols), t(d_2sls)) %>% as_data_frame()

# Add method and iteration variables

result_df %<>% mutate(

method = c("OLS", "2SLS"),

iter = i

)

# Return the results

return(result_df)

}Now for the simulation! We will run 10,000 iterations with sample size 1,000. It takes about a minute to run on my machine using three cores (I’m using proc.time() to track the start and end times of the simulation. Taking the difference gives us the elapsed time during the simulation.).

t1 <- proc.time()

# Run fun_iter() 10,000 times

sim_df <- mclapply(

X = 1:1e4,

FUN = fun_iter,

mc.cores = 3,

data = pop_df,

sample_size = 1e3

) %>% bind_rows()

t2 <- proc.time()

t2 - t1## user system elapsed

## 97.428 17.244 59.905Finally, let’s plot our results. First, \(\gamma_{21}\)—the coefficient on \(y_2\) in the first equation—which we know is actually equal to 2.

ggplot(data = sim_df, aes(x = y2, fill = method)) +

geom_density(color = NA, alpha = 0.9) +

geom_vline(xintercept = Gamma[2,1], color = viridis(3, option = "C")[2]) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0, color = "black") +

labs(

x = expression(Parameter~estimates:~gamma[21]),

y = "Density"

) +

ggtitle(

expression(paste("Simultaneity bias: Comparing OLS and 2SLS in estimating equation 1 parameter ",

gamma[21])),

subtitle = "10,000 iterations with sample size 1,000"

) +

scale_fill_viridis(

"Estimation method:",

discrete = T, option = "C", begin = 0.15, end = 0.85

) +

theme_ed

Repeat for \(\beta_{21}\) (\(=3\)) and \(\beta_{31}\) (\(=5\)).

ggplot(data = sim_df, aes(x = x2, fill = method)) +

geom_density(color = NA, alpha = 0.9) +

geom_vline(xintercept = Beta[2,1], color = viridis(3, option = "C")[2]) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0, color = "black") +

labs(

x = expression(Parameter~estimates:~beta[21]),

y = "Density"

) +

ggtitle(

expression(paste("Simultaneity bias: Comparing OLS and 2SLS in estimating equation 1 parameter ",

beta[21])),

subtitle = "10,000 iterations with sample size 1,000"

) +

scale_fill_viridis(

"Estimation method:",

discrete = T, option = "C", begin = 0.15, end = 0.85

) +

theme_ed

ggplot(data = sim_df, aes(x = x3, fill = method)) +

geom_density(color = NA, alpha = 0.9) +

geom_vline(xintercept = Beta[3,1], color = viridis(3, option = "C")[2]) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0, color = "black") +

labs(

x = expression(Parameter~estimates:~beta[31]),

y = "Density"

) +

ggtitle(

expression(paste("Simultaneity bias: Comparing OLS and 2SLS in estimating equation 1 parameter ",

beta[31])),

subtitle = "10,000 iterations with sample size 1,000"

) +

scale_fill_viridis(

"Estimation method:",

discrete = T, option = "C", begin = 0.15, end = 0.85

) +

theme_ed

Just as we suspected: 2SLS is providing consistent11 estimates of the structural parameters, while OLS is inconsistent in each application.

This requirement should sound pretty familiar, i.e., our old friend the exclusion restriction.↩

One of these exogenous (a.k.a. predetermined) variables should be an intercept.↩

I’m following Max’s notation here. Woolridge differs.↩

I’ve omit the \(t\) subscripts below.↩

Or \(-1\) if you are following Woolridge. Doesn’t matter.↩

Pun a little bit intended↩

Based upon Woolridge, Example 9.3.↩

Definition 15.1 for me↩

Page 219 in my copy.↩

Note: This kind of simulation (for a fixed sample size) is really getting at bias—rather than consistency.↩

Again, this simulation is more about unbiased-ness.↩